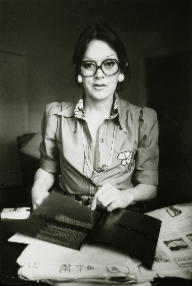

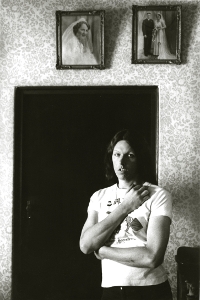

Socio-anthropological documentary Created: 1974-1975 An extensive portrait of the unique transvestite and transsexual community of Sydney, Australia. In 2003, Christopher Hirst of the The Independent, London, in his obituary about the publisher Anthony Mathews, describes Barry Kay’s documentary as “a groundbreaking photo-essay”. Publications: American edition – As a Woman English edition – The Other Women Australian distribution – The Other Women British Library, London; Shelfmark: YK.1922.b.9009 Preceding above publications, a feature appeared in the A portfolio of selected portraits from As a Woman Executed in monochrome, cover photo in colour |

|

Barry Kay’s preface to the book

During many return visits to Australia over the past fifteen years, I have seen the steady emergence of male transvestisism [sic; et seq] in Sydney and also the establishment of its large transsexual community. My interest in the phenomenon has grown as each time I became more conscious of the wide disparity that lies between this sub-culture and the society from which it springs. As a result I began the series of portraits that are now contained in this book.

I have aimed to depict the widest cross section possible – to show those living within a self-styled community or on the fringe of it and those choosing a more secluded existence. By its nature, the subject seems to defy clear definitions and to attempt to do so inevitably leads to generalisations. What can appear to the observer as a committed way of life, may only represent a phase of transition. There are many ambiguities and uncertainties within each personal situation and only one link seems common to all – the need to appear or to dress as the opposite sex. I have therefore purposefully avoided classification and for this reason the book is not divided into sections.

Sydney is Australia’s largest international city and its least conservative one, where many seek a more permissive climate. The city’s busy cosmopolitan tourist area, Kings Cross, is both the centre of entertainment and the adopted focal point for the transsexual community which comes from all parts of Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific. Here, many have found a livelihood by working in entertainment, particularly with the all-male revues for which Kings Cross and its environs are renowned.

Until recently more conventional employment for this community was unobtainable, leaving entertainment and prostitution as the principal means of survival in Sydney. However this has begun to change as wider public acceptance has increased their emancipation. Sydney’s transsexual community appears large by comparison to the population and noticeably more outlets are provided for employment than in most other international cities of its size. Throughout the Western world similar communities or ghettos exist, which not only vary in scale but differ widely through cultural influences. It was from the discussions while photographing in Sydney that I began to see how much national characteristics had conditioned the development of this particular sub-culture.

Australia’s colonization was firmly based on patriarchal foundations and in many respects it still retains theremnants of a Victorian morality. The characteristic features of the Australian male were derived from the days of the penal settlement, when the country was used by the British as a convenient repository for unwanted prisoners. Toughness, stamina and a mordant sense of humour were the convicts’ props in a forbidding exile. They developed a simple code of ethics and through constant fight against a harsh environment, created bonds of loyalty and a strong contempt for those who flinched. These conditions nurtured the sort of heroism made familiar through the exploits of Australian folk heroes such as Ned Kelly.

Until 1915 few Australians had travelled outside of their own country and the popular image of the Australian male was not known abroad until the First World War. At this time the Anzacs, combined armed forces of Australia and New Zealand, were shipped in their thousands to fight on the Gallipoli peninsular [sic] against the Turks, in defence of the Empire. Their endurance and immense courage in the face of appalling privations became a legend among their allies. From this was born the Anzac image with its stoic appeal to heroic sacrifice which exemplifies the Australian’s profound need to prove himself. It is a recurrent theme, best illustrated in the unique importance that the country gives to competitive sport, where the champion is usually elevated to hero status. Australia’s myth of heroism through physical achievement cultivates the belief in male elitism, a notion inevitably undermined by the presence of a transsexual community which, paradoxically, not only finds social acceptance but also manages to fulfil a social need.

Although an increasing number of males who openly adopt alternative roles may for some be symptomatic of a trend towards the greater merging of the sexes, in this instance it seems to point towards a reaction to the pattern of Australia’s male orientated society. Such a condition is of course familiar ground to anthropologists. Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead have both examined and compared widely differing cultural patterns, showing how primitive societies have institutionalised or repressed transvestisism in its different aspects. Examples of tansvestisism and transsexual communities recur throughout history, although as terms of definition they are of comparatively recent origin, appearing restricted in their meaning, especially where the dividing line is often not clear. Definition becomes even more limited when only describing one particular aspect – such as female impersonation.

Male transvestisim is well recognised but few instances are ever cited of its female equivalent. It has been suggested that because women are less subject to the taboo of dressing in clothes of the opposite sex, they are also less tempted by a forbidden act. Traditionally, the female has had more liberty to experiment with garments of the opposite sex. The fashion historian James Laver has explained how women have always been known to adopt various articles of male attire at moments of their emancipation or when they have felt that it was imminent. For the male, the act of putting on female clothing contains a far greater mystery and danger – this might also serve to explain the extent of its practice in a country given to such extremes in dividing the sexes.

In Germany, Magnus Hirschfeld first used the term transvestite for a major study on the subject, “Die Transvestiten” published in 19251. Hirschfeld was one of the chief pioneers2 in this field together with sexologists such as Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis. But at this time knowledge of the subject was only in its infancy and the use of hormone treatment and surgery did not exist for those who are now classified as transsexual3. It was not until 1953 that the term appeared, being employed as a further distinction by the authority in America, Dr. Harry Benjamin4, in order to describe those with such strong gender confusion as to require, in many instances, a physical conversion. It is this area that has become most widely known of recent years through reports of “Sex Changes” in the popular press.

Outside the medical profession, very little is understood or known about such conditions and even within scientific circles today there is still much speculation as to categories and origins, apart from any views for or against treatment. In his scientific report “The Transsexual Phenomenon”, one of the most comprehensive studies of the subject to date, Dr. Benjamin examines and endeavours to explain the infinite range of subtle variation contained within the phenomenon. He raised questions of congenital cause and of childhood conditioning as well a suggesting the influence of cultural differences.

The basic distinction that has been drawn between transvestite and transsexual image of himself as the opposite sex, whereas the transsexual is motivated by the feeling that he belongs to the opposite sex. Between these two states lie innumerable gradations and as predicted by the first person whom I photographed, never did I meet anyone whose condition appeared to be the replica of another. Transvestisism receives less publicity currently than transsexualism possibly due to more guilt surrounding the condition. Although not so familiar to the public, in fact its incidence is greater than transsexualism.

With an increasing acceptance of transsexualism in Sydney, in the past few years, there has been a noticeable willingness among transvestites to discuss their situation in the media. Their attachment to cross-dressing as understood in the clinical sense, involves some emotional and erotic stimulation and a certain amount of confusion with gender role. Feminine identification can be stronger for some than it is for others. In another instance, cross-dressing may also be a fetish. Although transvestisism is considered a less serious conflict than that of transsexualism, it is continually at odds with the Western tradition of strictly defining gender role. Australian society seems to express the extremes of this polarity. Most transvestites tend to lead homosexual lives and are often married with emotionally stable backgrounds, but the extent of their partners’ understanding varies considerably. In Sydney, members of the Sea Horse Club, an organisation for transvestites, have even devised an alphabetic scale to qualify this particular range of toleration. “D”, which is in the middle of the scale, represents antagonism and is typified by the case of a young wife who refuses to sleep with her husband on the grounds that she is not lesbian. They remain together only for the sake of their children, while every endeavour is made to restrain his attempts at gratifying the need for “dressing” elsewhere.

But it is homosexual transvestisism which first openly emerged in Sydney. Some living as women have found employment as such with or without their true identity disclosed. They do not necessarily resort to hormone treatment as in the transsexual situation and can therefore revert to a male persona if desired. The majority that I met tended to alternate their roles, depending on social circumstances.

Frequently “dressing” rituals can be highly elaborate with many hours of painstaking preparation in order to create the transformation. Although it could be interpreted simply as a form of justification, on several occasions transvestites suggested that their “dressing” was also a creative act, providing some artistic satisfaction. Such motivation I often heard from female impersonators who consider themselves neither as transvestite nor transsexual disliking the identification with either, some dispense with a pseudonym.

In certain respects, the two conditions are considered to be closely related since both share a gender disorientation and also wish to create the convincing image of a woman, whether as a private experience or in public. Crossdressing which is common to both conditions stops only at the point where the transsexual chooses to adopt women’s clothing on a permanent basis, often in conjunction with a conversion operation.

For transsexuals “dressing” is merely the outer shell. Transsexualism demands deeper commitment to female identification with a distinct need for physical transformation, through hormone treatment or surgery. Many transsexuals however pass through a short transvestite stage, and as Dr. Benjamin has pointed out, a transsexual’s concept of his condition frequently tends to alter once he is aware of the conversion operation as a possible alternative. Female identification then becomes so strong that it dominates all other aspects of life.

In one instance I encountered a group known as “The Synthetics”, whose pseudo-transvestite activities previously enjoyed notoriety in Sydney. Their “dressing” was a form of satire, more typically American in origin than Australian. One of its members gradually became the subject of the satire – now transsexual, he lives as a woman, has regular electrolysis and hormone treatment and intends shortly to undertake the conversion operation. At one of our photographic sessions, he related how his life had at different times been changed by two passing observations. The first was that he was an atheist, while pursuing a Jesuit vocation. The second, that he was transsexual, while engaged in satirising it. Each came as a revelation, resulting in complete reversal on both occasions.

Of recent years a sex reassignment programme has been instigated in Sydney, making the sex conversion operation officially available. Thorough investigation into each case is carried out to establish the validity of the patient’s claim and as this requires many interviews with long periods of waiting, many fear a negative result and turn to the alternative, private surgery. This eliminates the required psychiatric advice which most prefer to bypass. The expense of private treatment is considerable, though I know of several who would endure any temporary discomfort in order to save for surgery. In such cases this usually involves employment on day and night shifts, often supplemented by prostitution. Those who can afford it travel abroad to have the conversion operation, mostly in Cairo or Casablanca, for very few with whom I spoke were content with local results. Although their predicament is generally known throughout the transsexual community it does not seem to deter others from seeking treatment.

Occasionally suicide, or attempts at it, follow either unsuccessful surgery or simply failure to live with their condition. I often noticed among those that seemed most depressed, a tendency to deny their male aspect while identifying exclusively with their newly acquired “female” status. The more contented described how they had retained this duality, transforming the unwanted male persona into a dual femininity. A common example of this is where a day-to-day feminine role is alternated with a strikingly different personality, perhaps taking a glamorous or theatrical form at night. This kind of double existence I have also seen among those who are completely accepted as women in their employment, where the strain of self-scrutiny seems to require an antidote. To achieve this, one highly paid administrator who supervised the work of a group of female employees as a woman by day, works as barmaid near the docks by night.

Most recently, there have been increasing numbers of young people experimenting with hormones. This is perhaps symptomatic of the more general availability of drugs. Hormone tablets are reasonably easy to acquire in Sydney through several pharmacies that provide them without prescription. A number of teenagers, I suspect, were indulging in hormone treatment less from transsexual needs than from an attraction to the glamour associated with transsexualism. It struck me that this may be largely initiated by Sydney’s cult of the all-male revue which imitates a female stereotype – that of the glamorous showgirl. In European or American cultures, this stereotype supplies the fantasies to counteract domestic routine – in Australia, the role has more recently been delegated to men. It is a curious comment on the country’s social mores that its audiences will respond not to the original but to the synthetic copy.

Female revue now tends to enjoy less popularity than the all-male revue and this is further emphasised by the fact that many of Sydney’s strip club entertainers are transsexual. Sometimes they show considerable pride in deceiving the customers, thereby satisfying their ultimate aim of being accepted totally as women. This aim however, is more usually expressed through a desire to seek anonymity in complete seclusion. I have heard it claimed repeatedly that the real goal was for life as a suburban housewife, and those who have succeeded in finding a partner to realize that ambition are greatly envied. The cult of glamour, no matter how necessary a shield, still remains impersonal and the desire for a more genuine existence is always a dominant factor in their lives.

Wherever possible I have sought the authentic side, although at times this has been elusive. Some responded immediately to the idea of being photographed, readily dropping the artifice, while others needed reassurance, preferring to talk about themselves beforehand. These talks not only led to a better understanding of the subject, but have shown the consistent interest and concern of all those who most generously agreed to participate in this book.

Barry Kay, London 1976

The references in the footnotes, as well as the photograph of Magnus Hirschfeld, were kindly provided by Dr Rainer Herrn of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, Research Centre for the History of Sexual Science, Berlin. – The information was unavailable to Barry Kay at the time of researching the subject.